by Nan Thompson Ernst, Chief Steward

June 1, 2012

1976 – it was the bicentennial year when America commemorated its revolution and the national struggle to “form a more perfect union.” Such notions were on the mind of Library of Congress professionals when they formed a new union in 1976. Unknown to them, they were not pioneers. Library unions started in the 1930s had died away in the 1950s McCarthy era of loyalty and security programs and purges in the federal service. But on June 1, 1976, a charter was issued by the American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees for Local 2910 and a new union sprang to life. To its members, the union was simply known as the “Guild.” The founding members of our union set out to inform and educate colleagues about the union’s business and soon came up against their first big obstacle. The first contract was being negotiated and the union urgently needed to communicate to employees who would be working under the terms of that contract.

It seemed that Library management objected to the distribution of union literature. The internal mail was off limits. So union stewards and officers attempted to distribute newsletters and flyers at the desks of employees in our bargaining unit – a method of distribution known as the “desk drop.” Other employee organizations and clubs distributed literature to their members by desk drop without causing any problems. The Guild followed this lead and even took an extra step to make sure that desk drops were done after 5:00 p.m. to minimize disruptions in the workplace.

One of the early officers of the Guild, Cynthia (“Cinder”) Johanson, came to an office after 5:00 to place flyers on the desks. When she began, security was called and soon she was being forcibly “escorted” from the office and her union literature was confiscated. Busted! Security guards, forerunners to the LC Police, were often sympathetic to the union’s goals, but orders were orders. Union literature was confiscated from the desks of employees regardless of how it got there. As one of the security guards involved in this incident remembers, “We didn’t cuff her. That story that she was arrested and led out in handcuffs is an exaggeration! We just escorted her from the room,” he said. Johanson was later issued a disciplinary letter.

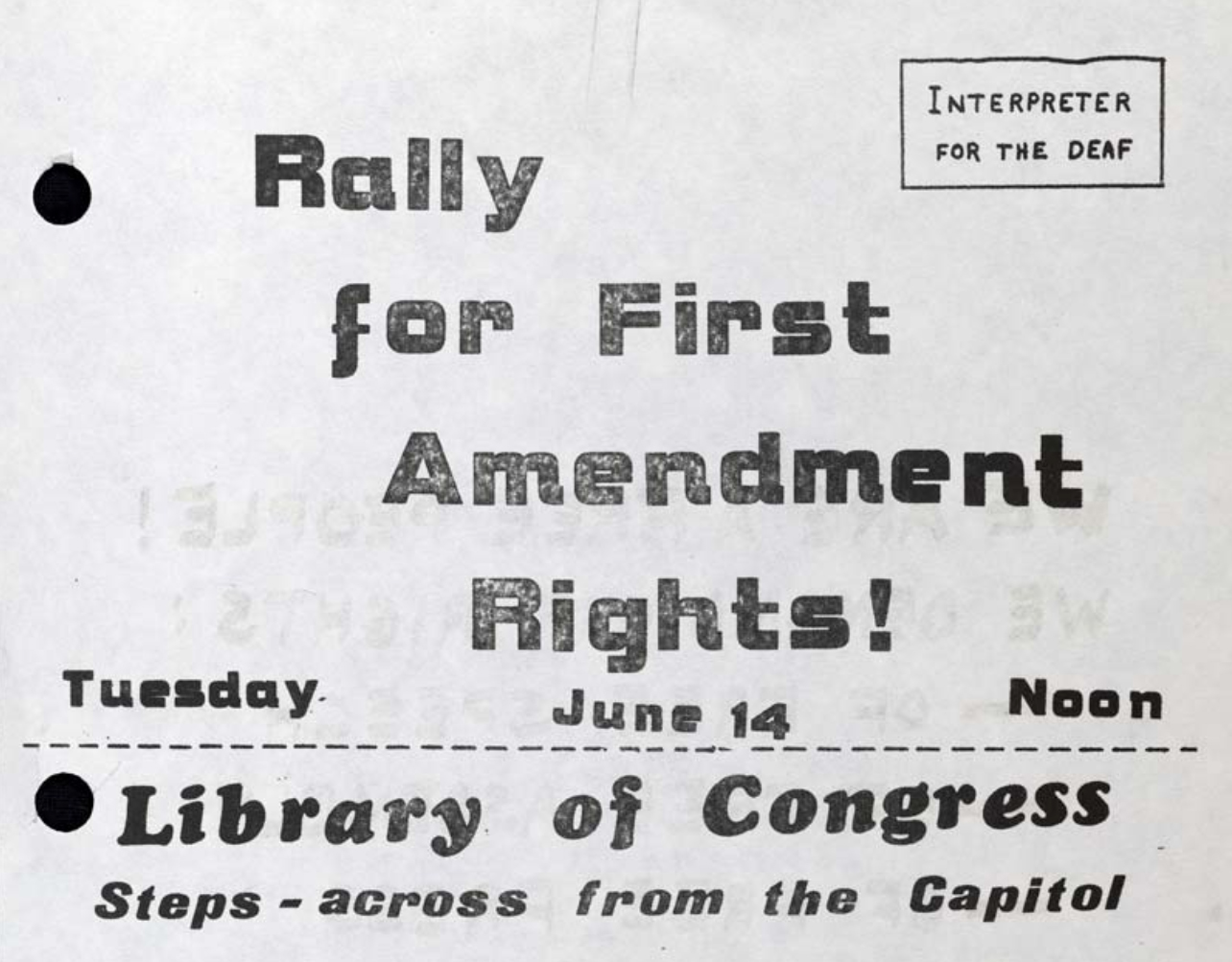

The Guild fought a campaign to overturn the regulations. The public campaign centered on calls for free speech. A rally was organized and 300 people assembled outside the Jefferson Building to protest the Library’s “gag rule.” One of the speakers, James Farmer from the Congress of Racial Equality, expressed his surprise and disappointment in having to speak for free speech on the steps of the Library of Congress. Farmer said, “I guess it just shows that you can lead an administrator to books, but you cannot make him think.” ACLU Associate Director J. Miller added “I am speechless that the greatest library in the world would restrict its employees’ freedom of speech!” Electronic copies of rally flyers are attached to the bottom of this document.

Guild officers were permitted to distribute flyers and newsletters outside the front door of the Library between the hours of 7:00 and 9:00 a.m. Some flyers carried a tag line “Read this if you dare!” Standing outside in the weather to hand out literature at the main entrance was a problem for many reasons, beginning with how to identify members. Thus flyers were passed out to everyone and then the union was rebuked for “molesting the public.” The Guild was permitted to set up a table in the cafeteria and to post notices on certain bulletin boards, yet these means of distribution could not reach everyone who was represented by the Guild.

The Guild also launched a legal campaign and charged the Library with an “unfair labor practice” for restricting distribution of its literature. The case was referred to an “umpire” who ruled that the Library must permit the Guild to distribute literature to desks if it permitted other employee organizations to do so. It looked like the Guild finally had a victory. But the Library’s response to the “umpire” was to prohibit all organizations from placing literature on employee’s desks.

The Guild detailed this controversy in the very literature which was being restricted and quipped in a newsletter that Librarian of Congress Daniel Boorstin was preparing a new chapter for his book, Americans, The Democratic Experience. The compromise which ended the controversy was that employees would be provided individual mailslots and Guild literature could be placed into those mail slots. It took several years to reach this compromise, but that is how we got our mail slots. The Guild was not allowed to use internal mail distribution until future contract negotiations established this right, but at least the literature could be placed in a mail slot and made available to employees represented by the Guild.

This illustrative story shows how far we have come and how hard the union has worked to make its place at the Library. We would never have made the tremendous gains of the last thirty years (flexible schedules, merit employment, grievance procedures and alternative dispute resolution, professional development, transit fare subsidy, credit hours, telework, leave bank, and many other provisions) if labor relations had remained at that primitive level. Incidentally, Cinder Johanson became a cataloging manager and had a long and distinguished career at the Library of Congress. The security guard who “escorted” her from the Library eventually joined the staff and became a member of the Guild.

Throughout the years, Guild officers and stewards labored to build solid, working relationships with managers and, bit by hard-won bit, the institution progressed. It is worth noting that the Guild relived this animus in recent years while defending its right to official time for union representational activity, to advocate for health and safety, to preserve the confidentiality of employees who seek assistance and information from the Guild, and the right of employees to assist the Guild without fear of penalty. While the Guild prevailed in those particular struggles, that animus is yet alive in Wisconsin and Ohio, to name some recent political actions to eliminate public-sector union rights. Legislation was introduced during the current Congress to eliminate official time for federal-sector unions. And so the struggle continues, as each generation of Library employees is called upon to find its voice and make a difference.

(An earlier version of this story was circulated by email on the Guild’s 30th anniversary in 2006)

Scanned copies of original flyers are included in this PDF.